Mapping spans from one document to another, an excellent interview question

Interviewing is arguably one of the worst parts of running a business. You can plan for success, and you can account for failure. When it comes to interviewing, neither applies.

To a certain degree this is certainly the very nature of the process itself. A company wants to hire the optimal candidate, whereas all candidates want to get hired. Thus, it is in the interest of the company to reduce barriers and design interviews in such a way to yield satisfactory results for everyone involved. One way to improve technical interviews is to create better interview questions.

Designing better interview questions

It is certainly appealing for candidates and companies alike if a candidate could (reasonably) demonstrate they can transfer their knowledge onto real world scenarios. In technical interviews, this can be tricky. Unless take-home assignments are given (which can, and will be cheated), how could a participant build something useful given the time constraint (usually 20-30 minutes). On the other end of the spectrum are purely memorisation-driven exam style interviews. Such exam style questions have very little useful character (arguably so, as even LLMs can ace them). A good level-ground is an interview question which teases the participant to demonstrate their knowledge, all the while not requiring memorisation.

The problem

In this blog post I will present a real-world problem which is suitable as an interview question. We will start with the most basic level, and quickly increase difficulty (and technicality). Given the following problem statement:

- you have a document with text

- the text can be further divided into units, such as sentences, spans (individual words), entities etc.

- you have two versions of a software that produce different assignments for the same text

- match the spans from one document to another

We could type the definition of this exercise like so:

from typing import NamedTuple

class Unit(NamedTuple):

id: int # the unique identifier of the unit

start: int # represents the start index of your unit

end: int # represents the end index of your unit

def map_documents(document_a: list[Unit], document_b: list[Unit]) -> list[int]:

"""

Maps units from document_b to document_a.

:param document_a: A document containing units.

:param document_b: A document containing units.

:return: The correct identifier for every unit in the document.

"""

passThis is a simplified real-world example of what will happen when you have an analysis from spaCy across different versions. In an interview we would also provide a concrete example of such an analysis:

doc_a = [Unit(0, 0, 10), Unit(1, 11, 20), Unit(2, 21, 30)]

doc_b = [Unit(0, 0, 10), Unit(1, 11, 15), Unit(2, 16, 19), Unit(3, 20, 30)]

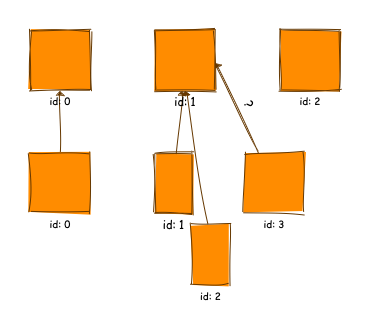

assert mapping(doc_a, doc_b) == [0, 1, 1, 1]A visual representation of this assignment might look like so:

The attentive reader might have already spotted that this problem requires a conscious design choice. Span 3 from document b spans two elements (both 1 and 2 in document A). A good candidate would spot this straight away, and ask the interviewer for clarification. At this point we could guide our interviewee and tell them that we will assign the first span preferentially. We might also ask them to discuss different possible solutions, including:

- assigning randomly (I am not kidding, for sorting algorithms this can be very valuable)

- assigning to the last span

- assigning to multiple spans

- assigning by overlap of the spans

There are different tradeoffs we can choose while implementing this. Depending on which choice we make, our architecture will become worse once we add new requirements to the software. We will discuss the different possibilities in a second. A seasoned engineer may spot them right away.

A first (naive) implementation

On a very basic level a participant can (and should) run a loop to solve this:

This code has a few limitations. In an interview it isn’t particularly important that you implement the right (or even correct) solution. Knowing why your solution may be bad is what truly counts. Let’s dissect some issues here:

- this code runs in \(O(n \times m)\) complexity which can be sub-optimal (as we will demonstrate in a second)

- the naive approach requires spans to be sorted in order and doesn’t allow for any other sorting

Before jumping ahead of ourselves with a better solution, we will extend the scope of our problem to demonstrate why problem number one can quickly become intractable.

Extending the scope of the problem

We can extend this problem with one simple addition:

- a document contains a sentence which contains one or multiple spans (of type unit)

Let’s update our types and method definition accordingly:

class Sentence(NamedTuple):

id: int # the unique identifier of the unit

start: int # represents the start index of your unit

end: int # represents the end index of your unit

class Span(NamedTuple): # unfortunately inheriting NamedTuple comes with complications

id: int

start: int

end: int

sentence: int

def map_documents(

document_a: tuple[list[Sentence], list[Span]],

document_b: tuple[list[Sentence], list[Span]]

) -> tuple[list[int], list[int]]:

pass

doc_a = (

[Sentence(0, 0, 10), Sentence(1, 11, 20)],

[Span(0, 0, 5, 0), Span(1, 6, 10, 0), Span(2, 11, 15, 1), Span(3, 16, 20, 1)]

)

doc_b = (

[Sentence(0, 0, 7), Sentence(1, 8, 20)],

[Span(0, 0, 5, 0), Span(1, 6, 7, 0), Span(2, 8, 15, 1), Span(3, 16, 20, 1)]

)

assert map_documents(doc_a, doc_b) == ([0, 0], [0, 1, 1, 3])We also update the corresponding diagram:

Without actually writing code, we could already ask our interviewee what implication for the runtime of our algorithm this would have (if we simply extended our naive implementation). A simple approach to justify this is:

- there are \(N\) sentences

- there are at least \(N = M\) spans (as every sentence has a least one span)

- using the naive implementation this algorithm runs in an optimal complexity of \(O(n^2)\)

With our participant having written merely seven lines of code, they could demonstrate that they:

- have an intuition of iterative problem solving (insofar as they ask the interviewer for more precise requirements for their solution)

- understand time complexity and its tradeoffs

Rewriting our code to be more Pythonic

So, how can we actually improve this code? The magic word in Python is the Iterator Type. Only if you have understood that Python’s built-in mechanics are all geared towards iterators, you have truly understood Python. The next step follows naturally:

def map_documents(

document_a: tuple[list[Sentence], list[Span]],

document_b: tuple[list[Sentence], list[Span]]

) -> tuple[list[int], list[int]]:

sentences_a = iter(document_a[0])

sentence_a = next(sentences_a)

spans_a = iter(document_a[1])

span_a = next(spans_a)

sentences_b = iter(document_b[0])

sentence_b = next(sentences_b)

spans_b = iter(document_b[1])

span_b = next(spans_b)

sentences = []

spans = []

while sentence_b is not None or span_b is not None:

if sentence_a is not None and sentence_b is not None:

if sentence_b.start < sentence_a.end:

sentences.append(sentence_a.id)

sentence_b = next(sentences_b, None)

else:

sentence_a = next(sentences_a, None)

if span_a is not None and span_b is not None:

if span_b.start < span_a.end:

spans.append(span_a.id)

span_b = next(spans_b, None)

else:

span_a = next(spans_a, None)

return sentences, spansWhile not very aesthetic, the idea is conceptually simple: open an iterator for all lists, and then loop from back-to-front. While I don’t expect many candidates to code this answer under time pressure, if they can outline the general idea (using one iterator per list) demonstrates perfectly fine that they understand Python.

The math behind this one is a bit more difficult to figure out but one can argue that:

- we have N sentences which typically match M sentences

- we have O spans which typically match P sentences

- in the best case O and P are identical to N

- thus the best-case complexity becomes \(O(4 \times N)\), which is a drastic reduction in runtime

Leveraging built-in data structures to avoid sorting issues

Suppose we are not interested in the optimal time complexity, but rather we want to know how we can address scenario two from our initial question list. How could we change our code such that it can be extended for this? Python has a built-in sorting algorithm that makes this possible, it is called bisect. Engineers know that sometimes a little upfront “investment” can help in the long run:

import bisect

sentence_mapping = {sentence.start: sentence.id for sentence in doc_a[0]}

sentence_mapping.update({sentence.end: sentence.id for sentence in doc_a[0]})

sentence_starts = sorted([sentence.start for sentence in doc_a[0]])

sentence_ends = sorted([sentence.end for sentence in doc_a[0]])

# get the sentence for span 3 in document a by ascending ordering

span_3_ascending_sentence = sentence_mapping[sentence_ends[bisect.bisect_left(sentence_ends, doc_b[1][3].start)]]

assert span_3_ascending_sentence == 1

# get the sentence for span 2 in document a by descending ordering

span_2_descending_sentence = sentence_mapping[sentence_starts[bisect.bisect_right(sentence_starts, doc_b[1][2].start)]]

assert span_2_descending_sentence == 1In this case we spent an initialization routine of \(O(4 \times N \times 2(N \times log(N)))\) complexity for the trade-in that we will be able to map any span in any order we like, incurring a \(O(N*log(N))\) cost. This is still significantly better than quadratic runtime, all the while giving us the flexibility to interact with a single element (instead of mapping the entire document).

A good engineer could come up with a similar solution without bisect (hint, timsort can do similarly well). The main goal of this exercise however is not to demonstrate working knowledge of sorting algorithms. What makes an engineer excell is his capability to design systems with flexible requirements.

Conclusion

The presented exercise gives an idea of what a (senior) engineering interview may look like. In such an exercise, everything can be used. Open-book, web search, ping-pong questions to the interviewer and so forth. Unlike a traditional coding puzzle, it challenges the participant to demonstrate critical thinking, and teases small, workable solutions (overall we have only written 55 lines of code). Its main goal is to “peel the onion”, iteratively unlocking more and more of the participants knowledge. The interview question is specifically geared towards Python development. Depending on your role, this obviously would need to be adjusted to be more relevant towards the end position. Regardless, I would hope it can help you inspire better interview questions.