Thinking is not hierarchical, why should AI be?

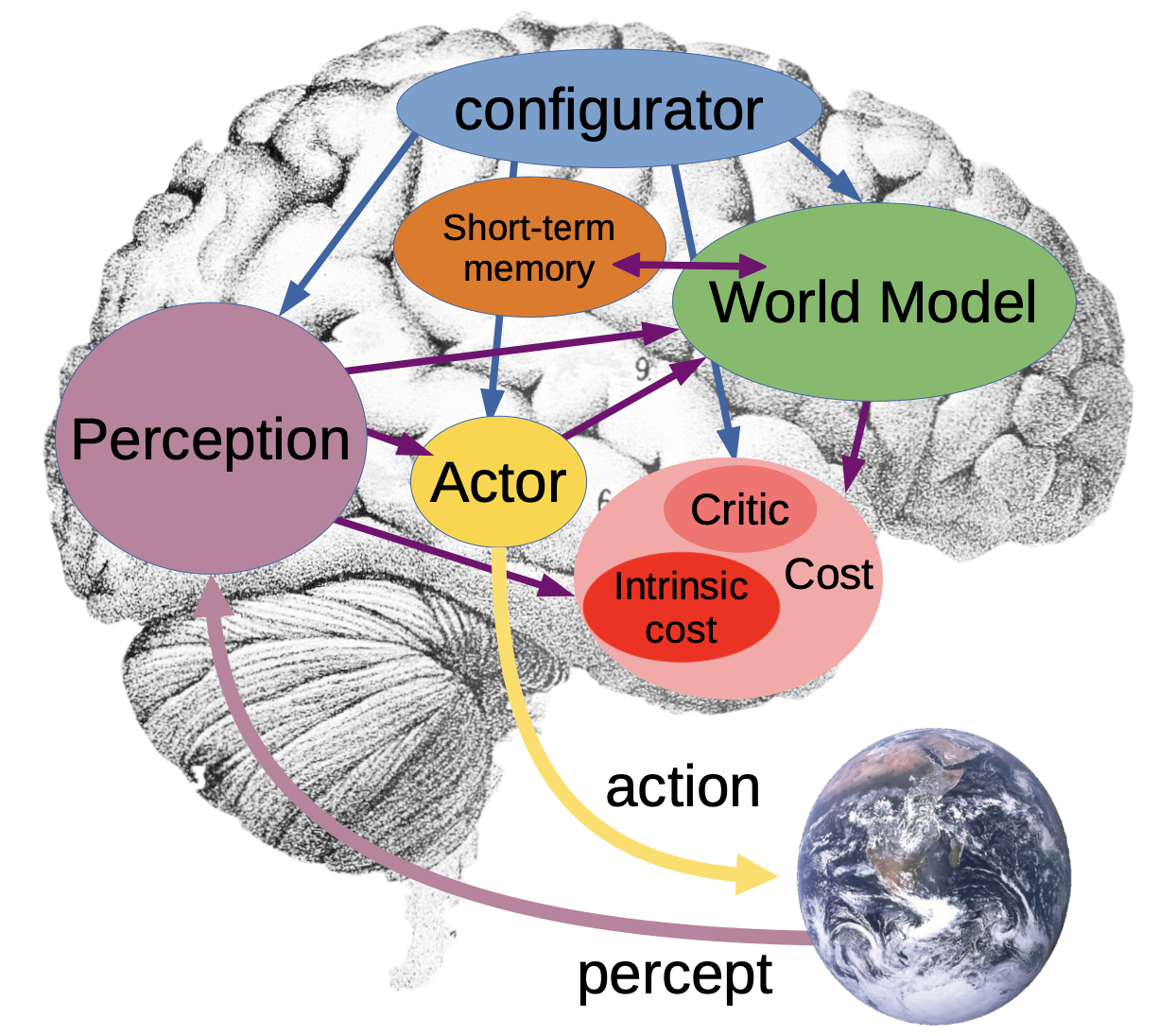

This blog post will discuss Yann LeCun’s paper (LeCun 2022) and a plethora of related ideas. Below is an illustration from (LeCun 2022) which summaries LeCun’s AI model:

LeCun imagines a set of hierarchical components which interact with each other. Most importantly:

- the percept which can perceive the world (e.g. multi-modal input)

- a world model which is built on top of the perception

- a cost component which reflects how “useful” the agent is in solving a problem

- a configuration component which modulates an actor to perform actions and directs the world model and perception

The whole system would be end-to-end trainable with the cost component providing the objective function for optimization.

The reason why LeCun’s paper is particularly intriguing, is because I believe it represents many ideas which are deeply embedded into the deep learning community. I will try to unravel and discuss some of these ideas.

Is learning optimization?

A prevalent sentiment in the machine learning community is “just use more compute and that’s that”. This is the message that some of the most important researchers in the field have been culminating after decades of research. Quoting Rich Sutton (Sutton 2019):

The bitter lesson is based on the historical observations that 1) AI researchers have often tried to build knowledge into their agents, 2) this always helps in the short term, and is personally satisfying to the researcher, but 3) in the long run it plateaus and even inhibits further progress, and 4) breakthrough progress eventually arrives by an opposing approach based on scaling computation by search and learning.

With the recent surge and success of large language models, many have argued this is indeed the case. We just “build bigger models” and eventually we will have machines which can learn. The concept that optimization equates learning is not a novel idea. In fact, Ian Goodfellow, whose Deep Learning book is widely regarded as “the bible”, notes very early on in his introduction to Deep Learning (Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville 2016):

Optimization algorithms used for training of deep models differ from traditional optimization algorithms in several ways. Machine learning usually acts indirectly. In most machine learning scenarios, we care about some performance measure \(P\), that is defined with respect to the test set and may also be intractable. We therefore optimize \(P\) only indirectly. We reduce a different cost function \(J(θ)\) in the hope that doing so will improve \(P\). This is in contrast to pure optimization, where minimizing \(J\) is a goal in and of itself. Optimization algorithms for training deep models also typically include some specialization on the specific structure of machine learning objective functions.

Origins of this ideology can be found even earlier, with the first “No Free Lunch Theorem” having formally been proven in 1995 (Adam et al. 2019). Core contributors of the deep learning community have strong beliefs that optimizing objective functions equates to learning. Everything can be learned, given enough compute, and a good optimisation method.

We should keep in mind this concept as we unfold LeCun’s paper.

One compelling argument against this position as it stands today, is that Moore’s law is on the limit of exhaustion, some physicists believe (Williams 2017). While theoretically a good approach, we may run into practical limits of how powerful computers can become.

Beyond compute, we also run into other obstacles. For instance, DeepMind showed empirically, to make large language models significantly more powerful, we will need several orders of magnitude more data than is currently available on the internet (Kaplan et al. 2020). Multi-modal training may alleviate some troubles, but real-world scalability imposes a significant limit to our current models.

Reality is not an unbounded problem

The machine-learning approach to problem-solving is often what I would like to call unbounded. We assume our problem domain runs in an infinite universe. Optimization methods converge from this unbounded function. For instance, a large language model is designed to predict the next token from a vocabulary and its previous input. The number of possible combinations in a sentence is (in principle) unlimited.

This approach is maximally flexible, and mathematically elegant. It also massively simplifies reality. I would argue, many problems have a very useful bound domain.

To give an example, we can turn to the vision domain. In the mammalian eye, light is detected in a way such that it is quickly collapsed into “useful” structures. We first recognize contrast in the retina. In the V1 brain layer, simple edges and their orientation are detected. In V2 we represent more complex shapes, such as contours. The hierarchy continues until we can recognise very complex shapes, such as individual faces. This condenses available information succintly into a format our brain can make (more) sense of.

If you are reading this fact (or studying brain anatomy for the first time), it may be quite baffling. Why does such a structure make so much “intuitive” sense. One could say, it comes almost “natural” to us. It turns out, it doesn’t just come natural, it is natural. (Carlsson et al. 2008) showed that hierarchical organization of images is very elegant and translates neatly into dense geometrical structures, when mapped into mathematical space. Evolution usually finds the optimum.

With this fact given, it is not surprising, that convolutional neural networks still contest the state of the art 1 in the vision domain.

Convolutional networks stand out as an example of neuroscientific principles influencing deep learning. — Ian Goodfellow(Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville 2016)

The essential three concepts powering CNNs are:

- Sparse interactions (selectively interaction only with a limited number of connections at one time)

- Parameter sharing (reusing the same function multiple times)

- Equivariant representations (changes in translation will not affect function)

Effectively, CNNs simulate receptive fields in the retina. We exploit the fact that small, meaningful features can be detected from patches of the input, rather than considering the entire (unbounded) input.

While we could brute force our way in an unbounded fashion with lots of compute, it is wasteful of resources. My argument is quite simply: even if optimization equates learning, it is not efficient.

Thinking is not hierarchical

I teased this point in the title of this blog post, but have not discussed it thus far.

In the vision domain, we have seen the brain organizes information hierarchically from the retina through V1 to V5. It is during this process that information becomes “available” to other parts of the brain. One can translate this in terms of LeCun’s AI model as the different modalities (visual, auditory, touch etc.) which represent the world model.

However, this is a greatly simplified idea of how information processing is done in the brain. For starters, information does not flow through different cortices linearly or hierarchically. Once more concrete shapes in V5 are activated, they may be used to build our current world (such as a conversation with our friend). There is no “man-in-the-man” (such as the configuration model proposed by LeCun) which singularly directs this information flow. This line of argument for consciousness is old and has been discussed to lengthy extent, and it has many limitations 2.

How then, does our brain direct the world model? To understand this (Petersen and Posner 2012) have conducted comprehensive studies into how attention, the mechanism of processing information efficiently, could work in the mammalian brain. To the best of our knowledge3, some important and useful processes take place at the same time:

- each modality learns an independant attention priority map which can distinguish what is useful, e.g a knife needs more attention than a spoon

- the brain modulates global alertness by preparing different areas of an incoming change

- an orienting network helps the corticess to decide which modality in which space (and time) to prioritize

The best analogy I can employ here is that of a forest and its inhabitants. There are a lot of things happening at the same time. If a tree falls, anyone within the vicinity of the tree needs to be aware of the fall. The tree will fall slowly at first and ever so rapidly. Many other trees are falling at a different pace. Thus, animals that wish to survive will handle priorities by how imminent the danger is.

Similarly, the brain will try a best-effort at directing available resources where they are needed. Unlike LeCun’s configurator model however, many different components act independently of each other, there is no central director to the underlying system.

An alternative path towards AI

For computer scientists, it is compelling to create joint-objective models. They are (usually) easier to train, and propagate less error. If strongly-hierarchical models are doomed to fail however, can we envision alternatives?

A few experiments have been carried out, which propose disjointly learned models which “speak a common language”. (Chang et al. 2019) proposed what they call Common Factorised Space. In their work they devised a new unsupervised objective function, which learns a common representation between multiple modalities (e.g. text and vision). This representation is leveraged as a new supervision signal to facilitate transfer learning. Their experiment showed clear improvements over jointly learned models on the same datasets.

The experiment carried out by (Chang et al. 2019) is a good first step into a new direction of decentralized models. I think there is much potential to be explored. If we can master common representation learning between models, we can optimise individual models by themselves. This creates new opportunity for considering e.g. the evolutionary aspects of existing brain architecture (and thus, make neural networks much more efficient).

Summary, or why should someone care?

Modern computing has allowed some to claim artificial intelligence has come within the grasp of reach of this era. However, the winner-takes-all approach of more compute may be unsuitable to reach this goal. It is already becoming exceedingly hard to scale our current models and make them more capable. The problem of “general” artificial intelligence is orders of magnitudes harder than predicting the next word (or the next action). Thus, if capabilities do scale logarithmically, it will be very hard (at best).

Even if we managed to achieve this result, the outcome would be uncertainty. If we train a general AI with an architecture that completely diverges from human intelligence, it will be very hard (if not impossible) to investigate. We are seeing the current wave of research trying to digest large language models, and all the societal implications that arise.

With decentralized intelligence that is more inspired by the brain, we have much higher chances of gaining any insight into the process along the way. This of course requires sacrificing some of the current paradigm, and the ease that goes along with it. We know how to optimize loss functions, and we’re getting better at it by the day.

Optimizing models disjointly however, is not very well researched. It is not surprising then, that many researchers would be hesitant to follow this approach. My hope with this blog post is to contrast the currently leading line of research into AI with an updated neuroscientific perspective, and why it may yield better models in the long run.

References

Footnotes

In May 2024 EfficientNet is leading the CIFAR-100 benchmark↩︎

For the interested reader, I recommend to study (Dennett 1990)↩︎

I highly recommend reading chapter 22 of (Kolb and Whishaw 2009) if you are interested in this topic↩︎